Amsterdam Avenue

#1111 (St. Luke's Hospital, near West 114th Street)

The historic hospital building at Amsterdam Avenue and 114th Street was designed by prominent socialite architect Ernest Flagg. The chapel of that hospital has stained glass and is the work of the same architect.

Photo: Chris Desantis

Avenue of the Americas

(Sixth Avenue)

#2 (near White Street)

Roxy Hotel (formerly The Tribeca Grand Hotel) post clock.

The new post clock installed May 5, 2000

in front of the Tribeca Grand Hotel.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, May 5, 2000.

Avenue of the Americas

(Sixth Avenue)

#390 (Between Eighth Street & Waverly Place)

Two working digital clocks.

Gives time but not temperature.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, Spring 1999.

Avenue of the Americas

(Sixth Avenue)

#425

Old Jefferson Library Tower.

Photo: Robert McBrien 2000.

Recent events

http://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/11/arts/old-bell-regains-its-voice-and-a-community-resounds.html

Avenue of the Americas

(Sixth Avenue)

#1221

McGraw Hill Sun Triangle

Less traditional is the McGraw Hill Sun Triangle in the sunken plaza in front of the McGraw-Hill Building. This very interesting fifty-foot high stainless steel sculpture denotes the passage of seasonal time by showing the relation between the sun and earth at the solstices. The three sides of the metal triangle point to the three seasonal position of the sun at solar noon in New York. The shortest side at the bottom points to the sun’s lowest position on the winter solstice around December 21. The longest side points to the sun’s position on the spring and fall equinox at noon around March 21 and September 23. The diagonal side points to the sun’s highest position on the summer solstice at noon around June 21. Perhaps, the most impressive feature of the triangle’s designs is that it casts during certain some parts of the year both a regular shadow as well as an “anti-shadow” resembling two hands of a clock on the plaza below. Next to the triangle is a depiction of the solar system engraved in the ground.

Avenue of the Americas

(Sixth Avenue)

#1325 (near 53rd Street)

Status: Working.

Photo by Tom Bernardin.

The Battery

Brooklyn Battery Tunnel

(Officially known as the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel)

Photo: Tom Bernardin

Battery Place at Hudson River

Pier A

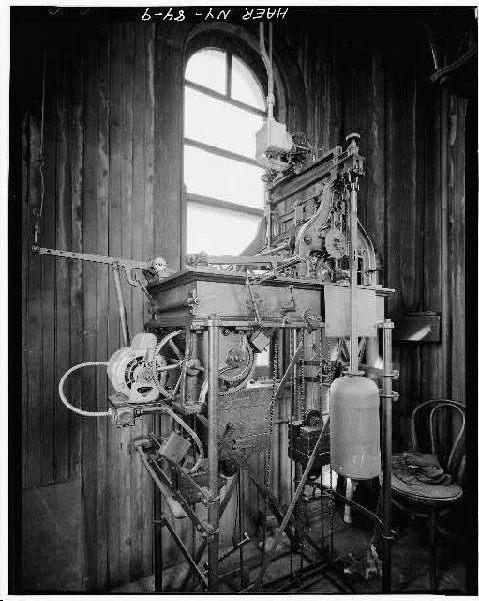

Clockwork Mechanism, west end clock tower.

Restored 2000-2001.

Photo 1: Tom Bernardin, Summer 2000.

Photo 2: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C

Recent events

Link to NY.Curbed-Inside Pier A

Bleecker Street

#384 (near Perry Street)

Taken down, location unknown.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, Spring 1999.

Bond Street

#1-5 (Between Broadway & Lafayette)

Working Clock.

Photo by Tom Bernardin.

Bowery

#58 (near Canal Street)

HSBC in Chinatown.

Not Working.

Photo: Vinit Parmar.

Bowling Green

Subway Entrance

Non-working clock.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, Summer 2000.

Broadway

#75 (Trinity Church near Wall Street)

In 1847 the Church paid local clockmaker James Rodgers a sum of $1,600.00, plus additional costs for the clock in the tower “required to be of the best materials and workmanship and warranted to keep accurate time.” It was assembled at his facility at 410 Broadway, a few blocks north of Trinity Church. At the time of construction the clock was the second largest clock in the world and weighed nearly four tons. One commentator noted that by building such a big clock, Mr. Rodgers “seems to have made an effort to see how much metal could be put into it.” The clockwork mechanism was placed forty feet above the dials and bells out of fear that the bell ringers might get caught in the powerful gears, something not unheard of in Europe. Thus, the movements of the hands were worked by tin shafts encased in long thin oak casings that ran from the mechanism to the dial.

Trinity’s chimes are the second oldest in the country, although, according to Owen Burdick, Trinity’s currently organist, the notes they sound have long been a mystery. Their maker, an eccentric German immigrant named Emil Waener who resided in Brooklyn, was chosen by Rodgers to create the design at the time of installation. Six bells were taken out of the second church, and after the biggest was recast, all six made their way into the third church along with four new ones. The largest of the bells weighed in at over three thousand pounds and the smallest seven hundred pounds. According to an article that appeared in the Brooklyn Eagle in 1875, “[A] rough wooden seat face[d] a frame work from which project nine long wooden handles. They are the levers fastened to thin lines connecting with the tongues of the bells. Besides the octave is the ‘baby’ bell, struck at the same time with any other bell. The tone of the ‘baby’ raised the sound one octave.”

The church members who hired Mr. Rodgers must have been pleased because keeping good time is what exactly the clock did. According to a Times article written in 1902, over fifty years after the clock was installed, it was reported that the “clock’s only claim to prominence is its immense size and its excellent timekeeping qualities. It is the largest in the city and one of the heaviest and best timekeepers in America.” The article goes on to note that “but for a slight interruption for occasional repairs [the clock] has been running ever since. Its interior is all on a larger and clumsy scale and the wheels, pinions, and cranks take up nearly the whole inside space of the large tower, and the friction is so great that constant oiling and care have been necessary all along to keep the clock in good working order.” Another article that described the clock’s weights and pendulum noted that, although the three dials of the clock were 8-feet in diameter [actually 10-feet], “there [was] enough power . . . to carry four 20 foot dials. Thanks to the heavy [18 feet long] pendulum, it does keep very fair time.” The clock was not only the country’s biggest but also was built with the second biggest dial in world at the time.

It took over an hour for two men to make about eight hundred and fifty turns to wind the seven hundred feet long, three inch thick rope that hoisted the 800, 1200, and 1500 pounds weights that powered the mechanism. The largest weight had a drop of fifty-feet, and if not for the bales of hay placed below it, serious damage to the foundation of the church would have resulted when the rope broke about a quarter century after the clock was installed. A local watch repairman by the name of Henry Fick was one of the men charged with the job of winding and servicing the clock for a better part of the nineteenth century. He was also contacted in the wee hours of the morning for an emergency repair on the first Christmas of the twentieth century when the clock stopped just a few minutes after midnight. To the people who lived in the neighborhood, the stopping of the clock was considered ominous, even taken as a sign that someone in the congregation would die within the week – no one actually died – a prevalent superstition of the time whenever a community clock stopped. Fick was able to get the mechanisms working again, but over the next few years more problems ensued.

In 1905, to the dismay of many, it became that the hands of time were winding down for the much loved clock, and it was replaced with current the #3 E. Howard clock guaranteed by the company to “tick regularly for 200 years.” The job of winding the new clock was far less demanding, and according to Owen Burdick that duty was handed over to his predecessors. The Elderhorst Bells Company eventually electrified both the clock movements and the bells, which still chime on the hour, the half hour, and the quarter hour as they have been doing for over a century and a half. As an interesting side note, in 1929, hundreds of pigeons were removed from the clock tower where they had found a warm resting place, but occasionally they got caught up in the gears of the clock. The tower windows, as in most clock towers today, have since been screened to keep such intruders out. One hundred years after being installed the clock is still running on time.

Broadway

#176

William Barthman Jeweler

Barthman, located in the sidewalk on the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane. Aside from the fact that it was specially made for the William Barthman Jewelers, established in 1884, not much else is known for sure about it. It is believed that the Self-Winding Clock Company installed the clock around the turn of the twentieth century, but it dates as far back as 1899 in some accounts. Since installation, it has received several facelifts, including a very durable cover made by NASA from the same glass used on the space shuttle that protects the clock’s face from the continuous foot traffic.

"In 1899, jeweler William Barthman installed a clock of his own design in the sidewalk outside of his jewelry store on Maiden Lane, in hopes of attracting more customers—it even lit up at night. The intersection of Maiden Lane and Broadway was the center of the city's jewelry district at the time, and got a lot of foot traffic, so the clock instantly captured plenty of attention... and a lot of feet upon its face." - Gothamist

Broadway

#209 (between Fulton Street and Vesey Street)

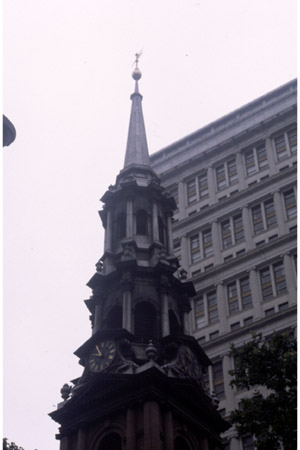

Saint Paul's Chapel. The oldest clock in New York City is found on the steeple of St. Paul's Chapel.

Photo: Wayne Beugg, June 2001.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, Chris Desantis

Broadway

#233

Metlife Building. The incredible three-story Self winding clock on the Metlife tower, ornamented with astonishing detailed marble and mosaic tile work, is perhaps the city's most impressive timepiece. It overlooks Madison Square Park.

Photo: Wikipedia.

Photo: Tom Bernardin

Broadway

#280 (Near Chambers Street)

Sun Building.

THE LOST HISTORY OF THE NEW YORK SUN CLOCK AND THERMOMETER

Photo: Vinit Parmar.

Broadway

#346 (between Worth Street and Leonard Street)

Click here to see the original court decision,

Early Coverage from The New York Times,

Recently written up in the Harvard Law Review.

The Clocktower Office Building.

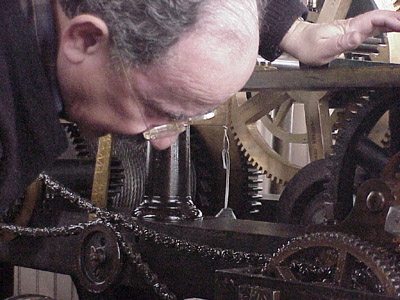

The clock was manufactured and installed by the E. Howard Clock Company of Boston, New York and Chicago for the New York Life Insurance Company in 1897.

Prior to 1980 the clock had not worked for at least twenty years and had not been lighted for night-time viewing for over thirty years.

It was restored, as a gift to the City of New York, by Mr. Marvin Schneider of Brooklyn and Mr. Eric Reiner of Spring Valley, New York. Both are New York City employees who donated their services, working on this restoration on their lunch hours and days off for more than one year. The New York Daily News of December 4, 1979 described their effort:

The clock is powered purely by a weight that can be raised either manually by usage of a large key or by a 3/4 horsepower electric motor. In the southeast corner cabinet is located a 1,000-pound weight which powers the time keeping part of the clock off which the four dials run. In the double-width cabinet on the northwest side are located two 800-pound weights which provide power to activate a 70-pound hammer which strikes on the hour.

The hammer and the bell which it strikes are located in a chamber above the clockwork. This chamber has louvers on all four sides which allow the sound to go out while minimizing the entry of rain and snow. The bell, weighing 5,000 pounds, is twice the size of the Liberty Bell. It was cast for the Howard company by the McShane Foundry of Baltimore in 1897. On the hour one can observe how a lever, attached to the works, pulls on a cable which activates the hammer in the room above.

The Howard Company, in a letter dated October 25, 1895, described the clock as a "No. 4 Striking Tower clock made extra large and heavy in all the parts where strength and size are required of HARD HAMMERED COMPOSITION, arbors and pinions of best OPEN HEARTH STEEL, frame and supports of CAST IRON, disconnecting device for the dial works arranged so that the clock can be readily set from inside the tower, cluster gear for...dial works properly arranged so that the clock can be used...on the Broadway end of the building, movement with Gravity Escapement, compensating two seconds pendulum...and a twelve foot sectional dial with hands, shafting, shafting and all material that will be required to set up the clock...".

The Howard Clock Company, still in business, discontinued manufacturing and servicing of tower clocks in 1964. They did, however, provide a replacement pilot-face and small gear located on the works.

This clock is unusual, especially in New York City, in that it is completely original. Many clocks, including the New York City Hall clock and the Jefferson Market Courthouse clock, have been electrified. The 346 Broadway clock, in its original state, still lives up to the Howard Company's guarantee to run accurate to within ten seconds a month.

Photo: Art Koch, February 2001, Jim McIntosh, February 2001.

Recent events

http://www.neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb_files/1987NewYorkLifeInsuranceBldg.pdf

http://tribecatrib.com/content/time-running-out-famed-clock-tribecas-clock-tower-building

http://www.cbsnews.com/videos/new-yorkers-want-to-save-clock-from-march-of-time/

http://www.lumichron.com/save-the-clocktower/

http://untappedcities.com/2011/12/05/lost-33-foot-high-8-ton-statue-have-you-seen-it/

Broadway

#366

Not working.

Photo Tom Bernardin.

Broadway

#488

The E.V. Haughwout Building is a five-story, 79-foot tall, commercial loft building in the SoHo neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, at the corner of Broome Street and Broadway.

Still Working.

Photo Tom Bernardin.

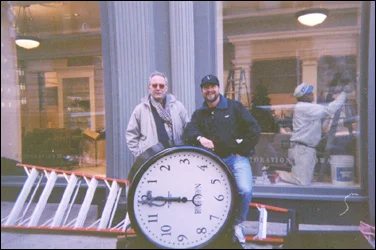

Broadway

#935 (near East 22nd Street)

Newly restored clock awaits installation by Ken Neill of The Verdin Company.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, Spring 1999

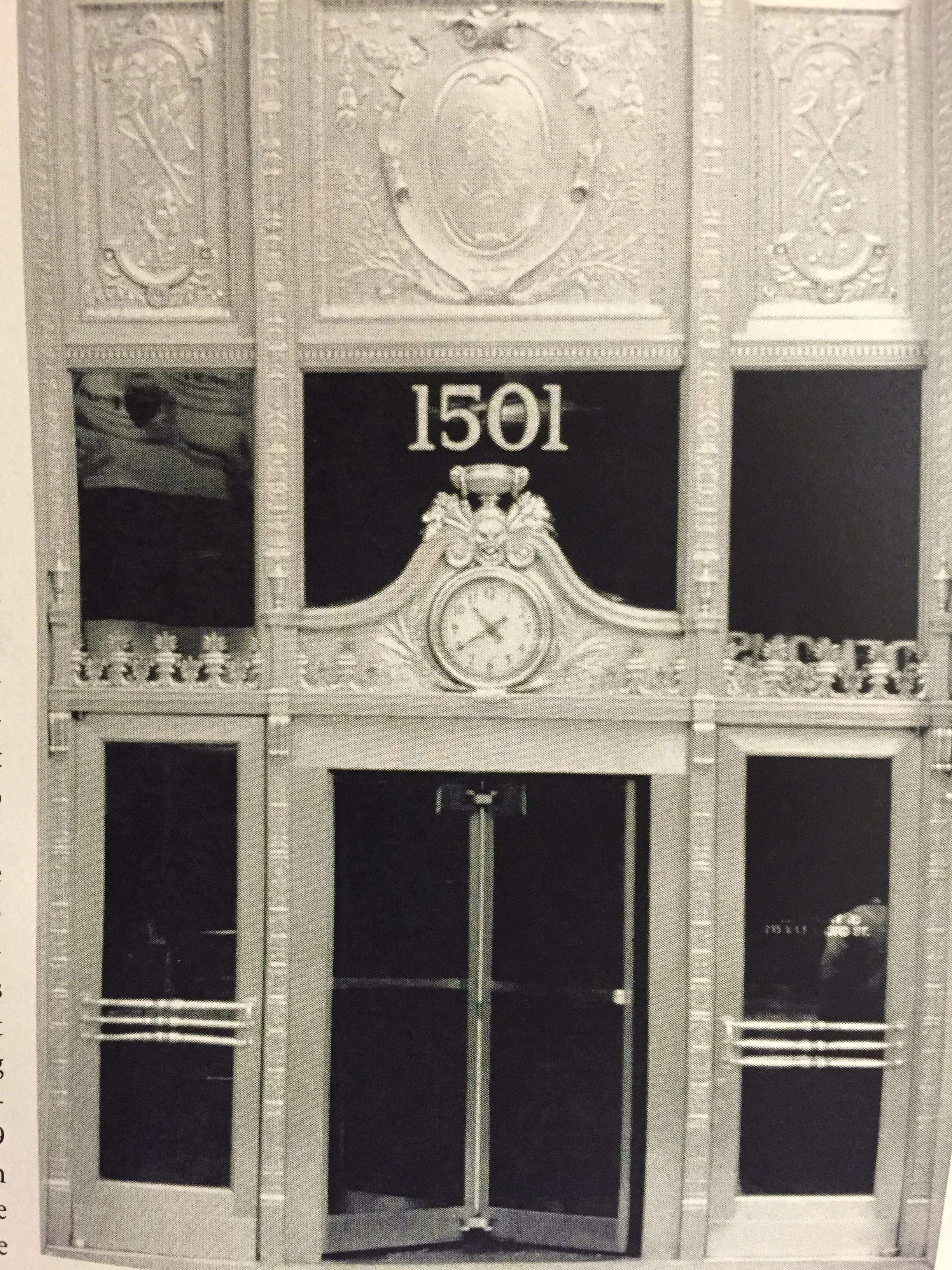

Broadway

#1501 (Between 43rd & 44th Streets)

The Paramount Building.

The clock on top of the Paramount Theatre was not only the highest point in Times Square, but once the highest point in all Manhattan north of the Woolworth Building in lower Manhattan. Today, the large clock face and globe are still one of the area's nicer sights despite the many new buildings. It is a working illuminated tower clock with 5-pointed stars in place of numerals.

The entranceway of the Paramount also retains this stylish clock above the door.

Photos: Susie Bernardin, Spring 2000. Entranceway photo by Vinit Parmar.

Broadway

#1515

(Near 44th)

Photo: Tom Bernardin

Broadway

#1650

Photo: Tom Bernardin

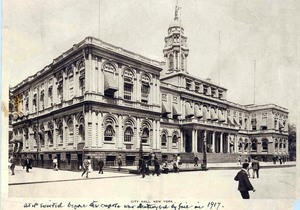

Broadway

City Hall Park

(between Broadway, Park Row, and Chambers Street)

Photo: Wayne Beugg, June 2001.

Center Street

#240

Old Police Headquarters

Chambers Street

#128

Non-working doorway clock.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, 2000.

Cooper Square

#30 (at Bowery & 6th Street)

Photos: Beth Sopko

Duane Street

#146 (between West Broadway & Church Street)

Photo: Vinit Parmar.

East 10th Street

#131 (St. Mark's Church, intersection of Stuyvesant Street & Second Avenue)

Clock maker, John Stokell installed the first timepiece in Saint Mark’s Church in 1828.

In 1828, the church steeple, the design of which is attributed to Martin Euclid Thompson and Ithiel Town, in Greek Revival style, was erected. More changes came about beginning in 1835, when John C. Tucker's stone Parish Hall was constructed, and the next year (1836) the church itself was renovated, with the original square pillars being replaced with thinner ones in Egyptian Revival style. In addition, the current cast- and wrought iron fence was added in 1838; these renovations are credited to Thompson. At around the same time, the two-story fieldstone Sunday School was completed, and the church established the Parish Infant School for poor children.

Later, in 1861, the church commissioned a brick addition to the Parish Hall, which was designed and supervised by architect James Renwick, Jr., and the St. Mark's Hospital Association was organized by members of the congregation. Outside the church, the cast iron portico, was added around 1858; its design is attributed to James Bogardus, who was an early innovator in cast iron construction.

At the start of the 20th century, leading architect Ernest Flagg designed the rectory.

Photo: Chris Desantis

East 18th Street

#121 Not working.

East 42nd Street

#12

Nat Sherman

Photo: Chris DeSantis

East 42nd Street

#89

Grand Central Terminal

Photos to follow

Recent Events

http://gothamist.com/2013/02/01/14_photos_of_a_grand_central_youve.php#photo-1

East 42nd Street

#89

Grand Central Terminal

Photos to follow

East 42nd Street

#89

Grand Central Terminal

19th Century Self-Winding Railroad Clock

Photo: Chris DeSantis

East 53rd Street

#307 (Between 1st & 2nd Ave)

Once part of a larger factory complex built by a cigar rolling company, the recently refurbished Timekeeper Building is the only former factory in Manhattan to retain a clock.

Photo: Vinit Parmar.

East 55th Street

(Near Madison Ave)

Photo: Vinit Parmar.

East 57th Street

#12 (near Madison Avenue)

Tourneau Time Machine.

E. Howard clock mechanism on display.

The Verdin Company.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, 1998.

East 57th Street

#41 (near Madison Avenue)

Fuller Building.

Non Working doorway clock.

Photo: Tom Bernardin, Spring 1999.

East 60th Street

(near Lexington Avenue)

Taken down around 1979. Where is this clock?

Photo: Becket Logan, November 1973.

East 64th Street & Fifth Avenue

Central Park Arsenal

Constructed in 1851, the building predates Central Park in which it is currently located. Designed to resemble a medieval castle with eight battlements, it originally housed munitions for the New York State National Guard. In 1853, the State seized the land the building sits on and granted it to the city to build Central Park. One year later, the city purchased the Arsenal for $275,000, removed all the arms, and established park administrative functions on the premises. The building subsequently became home to the 11th Police Precinct and afterwards the American Museum of Natural History before the museum moved to the other side of the park. By the turn of the century, the building was deteriorating, but it was saved by a $75,000 face-lift in 1922, which included a new central turret with a clock installed by the E. Howard Co. Today the Arsenal houses the New York Parks and Recreation Department, the Central Park Administrator, the City Parks Foundation, the Historic House Trust, the New York Wildlife Conservation Society, the Parks Library, and the Arsenal Gallery.

East 64th Street & Fifth Avenue

Central Park Zoo.

The most playful of all the city’s timepieces is the Delacorte Clock situated near the entrance to the Central Park Zoo. On its top are two bronze monkeys that strike a bell on every half-hour, while six bronze animal figurines march in a circle at the base to one of thirty-two nursery rhymes. The scene is set in motion from a signal transmitted from a computer in a nearby building. The dancing animals include a goat playing the pipes of Pan, a hippopotamus playing a violin, a penguin playing a drum, a kangaroo playing a horn, an elephant playing a keyless accordion, and a bear playing a tambourine. The clock was erected in 1965 as gift from publisher and philanthropist, George T. Delacorte, who wanted to build a glockenspiel comparable to those found in Europe.

Photos: Tom Bernardin, Spring 1999; Chris Desantis.

East 72nd Street

Near 5th Avenue

The Waldo Hutchins Bench is the most notable of all the benches in the park because of its unique time keeping qualities. The large marble bench, a gift from August S. Hutchins, measures four-feet high by twenty-seven feet long, and has a very interesting bronze timepiece in the form of a tiny woman on the top of its middle portion. Semicircular lines inscribed in the slate at the front of the bench mark shadows cast off the sculpture at 10:00 am, high noon, and 2:00 pm during the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. A shadow is also cast in the hemicycle, which is the curved metal recede carved into the top of the bench that is configured with lines to indicate the hours. Etched into the back of the bench are the words “Alteri Vivas” “Oportet Si Vis Tibi Vivere” and “Ne Diruat Fuga Tempor Um,” meaning “You should live for another if you would live for yourself” and “Let it not be destroyed by the passage of time.” Designed by architect Eric Gugler, the bench was mounted in the park in 1932. The carved white marble stonework is believed to have been sculpted by Corrado Novani and the Piccirilli Brothers Studio, and the sundial was designed by Albert Stewart, although the tiny bronze woman at its center is attributed to Paul Manship.

Click Here for Central Park Website.

Photo: Chris Desantis

East 77th St

#100 (near Lexington Ave)

Lenox Hospital

Photo: Vinit Parmar.

Mid-Park at 79th Street

(Near Belvedere Castle)

Sundial enhances the Shakespeare Gardens on the west side of Central Park at the base of Belvedere Castle. The gnomon on the four-foot tall, stone sundial faces north, a principal discovered by the Greeks that allows for precise time-tracking.

East 21st Street

#170

Harlem Justice Center. A brick and brownstone Romanesque Revival Building, built in 1893, to serve as the Municipal and Magistrate's courts.

Photo by Vinit Parmar.

East River Bikeway

#6

Downtown Manhattan Heliport

Photo: Tom Bernardin

Eighty Sixth Street

#472

Photo courtesy of google images